R.I.P., Anita Roddick

Posted on September 11, 2007 by kateharding

Posted on September 11, 2007 by kateharding

Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop, has died of a brain hemorrhage at 64.

Roddick was well-known for her charity work and her amazing efforts to make it clear that The Body Shop has corporate values other than profit. Those values are listed on the website next to the slogan “Made with Passion”:

Against Animal Testing

Support Community Trade

Activate Self Esteem

Defend Human Rights

Protect Our Planet

I want to talk about the third one.

In 1998, I was into my second year of living as A Thin Person for the first time since I’d hit puberty, having lost 65 lbs. in 1996-7. I didn’t know — well, more accurately, didn’t believe — that two years later I’d be fatter than ever. I thought of myself as the rare dieting success story — a belief supported by my Jenny Craig counselor asking if I’d like to submit my before and after photos for a chance at being in one of their ads, as the smiling thin woman right above the “Results Not Typical” fine print.

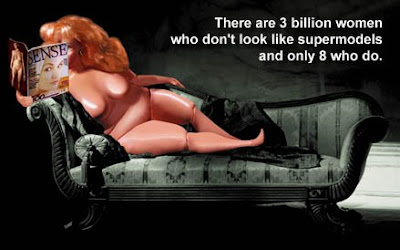

One day, on one of the manic, hours-long walks that helped sustain my weight loss, I passed a poster featuring a naked, fat, redheaded Barbie-type doll reclining happily on a couch, with the slogan,

“There are 3 billion women in the world who don’t look like supermodels, and only 8 who do.”

I stopped and stared. I didn’t even register for a couple minutes that it was an ad for The Body Shop. I just thought it was the coolest thing I’d seen in a really long time.

I stopped and stared. I didn’t even register for a couple minutes that it was an ad for The Body Shop. I just thought it was the coolest thing I’d seen in a really long time.

I went to the Body Shop and got myself a postcard of the same ad, and put it on the wall above my desk. Meanwhile, I still thought I was a dieting success story. And yet meanwhile, I still thought my thighs were too fat. I still wanted to be thinner — if I tried harder, I could be a size 2, not just a 4! I still hated my weak chin and big nose and problematic skin. I did not personally want to look like “Ruby” ever again, and yet, I couldn’t stop looking at that picture of her every damned day. I loved it. I loved her. I just thought I would never, ever be able to be as comfortable in my own skin as that plastic doll. I thought I would never, ever be content with my lot as one of the 3 billion.

These days, my body looks an awful lot like Ruby’s, actually — only with nipples and pubic hair and stretch marks and zits and freckles and skin tags and scars. And I am very comfortable in it. And Ruby is partly to thank.

I’ve had cause to say frequently over the last few days that body acceptance is not something I arrived at overnight, as if the logic just clicked and that was that. It was a long, painful struggle. And for a long time, I really liked the idea of fat acceptance, while still really, really not wanting to be fat — so as I’ve also said frequently in the last few days, I have a lot more empathy for fat acceptance supporters who still want to diet than it might seem like I do.

Coming to love my body for what it is — a fundamental part of who I am, not something separate from the Real Me, and most importantly, not an enemy of the Real Me — was a gradual process, most of it happening below my conscious awareness. But there were major flashpoints that will always remain fixed in my memory as early fat acceptance epiphanies. Reading No Fat Chicks, when I was still on Jenny Craig (the first time). Reading The Obesity Myth, after I’d done Jenny Craig and Weight Watchers more than once each, lost a total of 110 lbs., gained it all back, and was finally ready to stop fighting my body. And standing on that street in Toronto, staring at that Body Shop poster.

There are 3 billion women in the world who don’t look like supermodels, and only 8 who do.

On Anita Roddick’s website, she wrote in 2001 about the controversy surrounding the Ruby campaign. Mattel sent a cease-and-desist letter in the U.S., arguing that Ruby made Barbie look bad. (Roddick: “I was ecstatic that Mattel thought Ruby was insulting to Barbie — the idea of one inanimate piece of molded plastic hurting another’s feelings was absolutely mind-blowing.”) In Hong Kong, the posters were banned for being too titillating — while genuinely provocative images of real women remained.

Says Roddick:

And there, in a nutshell, is my relationship with the beauty industry. It makes me angry, not only because it is a male-dominated industry built on creating needs that don’t exist, but because it seems to have decided that it needs to make women unhappy about their appearances. It plays on self-doubt and insecurity about image and ageing by projecting impossible ideals of youth and beauty.

Leonard Lauder, son of Estée, once refused to advertise in Ms. Magazine (back when they still accepted ads) because, he said his products were meant for “the kept woman mentality.”

I think it is a moral imperative that The Body Shop, as a cosmetics company itself, continue to buck the industry on issues of self-esteem, and to expose the cruel irony of the myth that a company must make a woman feel inferior in order to win her loyalty.

They did buck the industry — long before Dove’s much talked about Real Beauty Campaign — and they did create change. Not to mention, they did create brand loyalty without playing on women’s fears. (Mmmm, Body butter.) Believing that all that can be done doesn’t seem so crazy now, but it did when The Body Shop started doing it.

I will always be grateful to Anita Roddick for Ruby, just as activists for animal rights, the environment, HIV awareness, domestic violence awareness, human rights and numerous other causes are grateful to her for making The Body Shop a powerful force for good.

Thank you, Anita Roddick.

Rest in peace.

The Body Shop's campaign offers reality, not miracles.

By STUART ELLIOTT

By STUART ELLIOTT

CAN a plump plastic doll help change the way that fashion, beauty and cosmetic marketers portray women in advertising?

The Body Shop, an iconoclastic retailer that sells creams, soaps and other products primarily to women, hopes so. The chain, which has been suffering sales declines in this country in the face of intensifying competition, is undertaking a rare campaign in the mainstream American media, which carries the theme ''Love your body.''

The campaign is emblematic of the hotly debated issue of the ability of advertising to affect and influence behavior. Print advertisements and posters are focused on self-esteem and self-image and centered on the doll, nicknamed Ruby.

The reason for that sobriquet is obvious after seeing the toy, which appears in an ad in the September issue of Self magazine and on the posters due to go up in Body Shop stores for two weeks beginning in mid-September. Though Ruby's red hair, blue eyes and pert nose are typical of so-called fashion dolls, her body is definitely not.

The doll's breasts, stomach and thighs are in a word, Rubenesque. She reclines on a green velvet sofa under this headline: ''There are 3 billion women who don't look like supermodels and only 8 who do.''

''Most of the cosmetics industry bases its communications on stereotypical notions of unattainable ideals,'' said Marina Galanti, head of global communications at the Body Shop International P.L.C. in Littlehampton, England. ''We're asking for a reality check.''

''The images in the barrage of advertising around you have very little to do with people riding the bus with you, sitting in the office with you, having dinner with you,'' said Ms. Galanti, who is responsible for advertising and marketing. ''It's good to step back once in a while and say, 'Hmmmm.' ''

The Body Shop campaign, created in house, is indicative of a growing trend: sales pitches that mock or tweak conventional methods of peddling products, particularly images that are perceived as persuading women to conform to certain ideals of appearance. That trend has intensified in the 1990's with the formation of activist groups like Stop Anorexic Marketing, an organization founded by women in the Boston area, some of whom suffered from eating disorders.

For instance, ads for Dove beauty bar promote that Unilever product as ''for the beauty that's already there.'' Campaigns for Chic jeans from the Henry I. Siegel Company have carried such themes as ''Look like yourself'' and ''It's what you feel that counts.'' Print ads for the Freeman Cosmetic Corporation feature a woman, her back turned to the camera, asking, ''How much do you need to see to know I'm beautiful?'' And an ad for Special K cereal, run in Canada by the Kellogg Company, that depicted an ultrathin model and carried the headline ''If this is beauty, there's something wrong with the eye of the beholder.''

''It's enlightened self-interest to identify yourself with women who will be drawn in by advertising that doesn't show an anorexic 15-year-old,'' said Susan Weidman Schneider, editor in chief of Lilith, a quarterly women's magazine from Lilith Publications Inc. in New York that has run articles on subjects like self-esteem and self-image.

''Say what you will about the Body Shop trying to reclaim market share,'' she added, referring to the chain's loss of sales to rival retailers like Bath and Body Works, H20 Works and the Gap. ''The campaign is terribly clever.''

Ms. Galanti said: ''In terms of competition, it's good to celebrate our points of difference. And Ruby does that.''

Most ads by Body Shop International have appeared in stores, devoted to cause-related marketing programs like voter registration. The company has advertised only sporadically in American media, primarily in small, so-called alternative publications like Lilith and Mother Jones.

''Our approach to advertising has been sort of experimental,'' Ms. Galanti said. ''This is a trial for taking alternative imagery into the mainstream media. There are a lot of interesting possibilities there, even for companies oriented toward unorthodox methods of communication.''

If that evokes the strategy pursued by Benetton Group S.p.A. -- the Italian apparel retailer notorious for campaigns that advocate stands on contentious social issues -- well, Ms. Galanti spent four and a half years overseeing international communications and media for Benetton.

''I don't have a problem with advertising as a tool for activism,'' Ms. Galanti said. ''The more interesting way to use advertising is to make brand statements, saying more about our brand than our product.''

Body Shop International initially thrived in America with proclamations by its founder, Anita Roddick, on disputatious issues like animal rights and ecology. The Ruby campaign, though still issue-oriented, is more narrowly focused on a topic more relevant to a purveyor of ointments, lotions and potions.

''It's not a question of what we're trying to tell people, but of what we're not trying to tell people,'' Ms. Galanti said. ''We're saying our products will moisturize, cleanse and polish; they will not perform miracles.''

Ruby's arrival in America comes after she appeared in ads in several of the 47 countries in which Body Shop International operates stores, including Australia, where newspapers there coined her nickname, and Switzerland. In Britain, Simon Green, creative partner at the BDDH agency in London, praised the campaign last month in a critique for the newspaper The Independent as ''incredibly powerful'' because ''it shows enormous empathy for women.''

In addition to the Ruby print ad and posters, there will be what Ms. Galanti called ''Ruby approval stickers'' in stores, which consumers can affix ''on images of men and women they agree with.''

Ruby is an element of a three-part campaign with self-esteem motifs from Body Shop International. After the focus in September on body image, Ms. Galanti said, October will be devoted to ''self-esteem and activism,'' in the form of a promotion to sell whistles that symbolize what a coming print ad calls ''the urgent need to stop violence against women.'' And in November, Ms. Galanti said, the focus will be ''self-esteem and aging -- wrinkles.''

No comments:

Post a Comment